The Money Book: How to Implement a Percentage-Based Budget to Manage Your Finances

A system for independent workers with inconsistent paychecks to manage their money.

How do you manage your money?

Maybe you use a zero-based budget, assigning every dollar a job and putting your money to work.

Or maybe you follow the 50/30/20 method to help you allocate your paycheck between wants and needs.

Or maybe you don’t budget at all. Instead, you prefer to just keep an eye on your spending, making sure you stay within your means.

It doesn’t matter what your personal money philosophy is, but having a plan is important. You want to make sure your money – and the time you spend earning it – aligns with your goals.

The point of work isn’t so much about adding as many commas to your bank account as you can, it’s about making progress toward your goals.

The Money Book by Joseph D’Agnese and Denise Kiernan presents a financial management system designed for non-traditional workers like freelancers, part-timers, and self-employed business owners. Instead of creating a budget based on a regular biweekly paycheck, the authors offer a different process for prioritizing spending based on irregular and inconsistent income.

This article will cover the main thesis of the book, highlight some of its flaws, and emphasize why having a plan for your income is important, no matter how infrequent it may be.

The nature of work is changing. American workers need a better system to manage their finances in order to accommodate the changes underway.

Published in 2010, The Money Book is a bit dated but brings attention to a growing trend of decentralized work. Over the past few decades more and more responsibility for employment has fallen on the shoulders of workers.

Take retirement as an example. Companies used to provide pensions for loyal workers. Now workers have individual retirement savings plans. Whether it’s a 401(k) or an IRA, everyone is responsible for saving enough for their own retirement while also being responsible for learning how to properly play the stock market too.

Instead of cutting benefits, employers are starting to cut workers altogether. Think of gig economy companies like Uber and DoorDash. Rather than hiring workers outright, these companies classify the people who provide services in the company’s name as independent contractors.

According to Upwork, 38% of American workers are freelancers or independent contractors. As artificial intelligence and automation is poised to displace even more workers, it’s likely the number of people engaged in self-employed work activities will grow in the coming years.

The shift from employer-provided work to self-employed work is a monumental transition especially when it comes to how you manage your money. W2 workers are accustomed to earning a bimonthly paycheck. You can depend on it hitting your bank account on time and it’s easy to plan a budget around.

Self-employment is an entirely different game. You have to constantly hustle to find work. When you do, you won’t get paid for weeks – if not months – after you submit your final deliverable. Some clients pay promptly when you submit an invoice, while the brutal truth is others might not pay at all.

When you have inconsistent income that varies from month to month, it’s hard to plan for regular expenses let alone save for retirement. The authors of The Money Book propose a new system of personal financial management for workers who aren’t earning a regular paycheck. While the authors are freelance writers themselves, the system they propose isn’t limited to just freelancers. It can also work for independent consultants, contractors, temp workers, and gig workers.

The goal of the system is to provide a financial safety net for yourself that replicates the kind of safety net your employer used to provide you. Paying taxes, saving for retirement, taking paid time off, and paying a portion of your health insurance premium are all things you get working for an employer. When you work for yourself, you are responsible for all of these things, on top of making enough money to cover your cost of living.

As the economy changes more people will be thrust into self-employment. Workers who are used to consistent income might not have the right plan in place to manage their finances. This can spell trouble when work dries up or a client fails to pay an invoice.

Cash flow – not income – is one of the biggest challenges freelancers will face. The purpose of adopting a new financial management system is to help freelancers avoid falling into debt. The authors note:

“In other words, [independent workers] got so much debt that it’s crippling their ability to handle current bills, while the future goes unplanned and unfunded.” (24)

The Money Book recommends a system that prioritizes spending and establishes a hierarchical process to determine how much money you can spend and how much you should save for the future.

Cash flow is managed in two categories: income and expenses. Surpluses can be used to repay debt or invest in the future.

The Money Book simplifies money management into two primary categories: what you earn and what you owe. These two categories form the foundation of the system recommended in the book.

The authors assume that the book’s readers are in debt. In fact, an entire chapter is devoted to paying it off. That’s notable considering that beyond saving for retirement, the book makes little reference to investing or building wealth.

Debt is assumed to be a third category in the recommended money management system but I’m going to take the liberty to modify that to be a general surplus. To build a successful financial management system you need to earn more than you spend; however, you can allocate any surplus at your discretion. If you have debt you want to pay off, put it towards that. If you don’t and want to build wealth, invest what you don’t spend.

When it comes to expenses the book references two primary types: fixed and discretionary. Your fixed expenses are bills that don’t change from month to month while your discretionary expenses are everything else. Rent, your phone bill, and a Spotify subscription would fall into the former category while groceries, gas, and dinners out would fall into the latter.

Again, I’m going to take some editorial liberty to modify these categories. Personally, I look at expenses as mandatory, obligatory, and discretionary then break those down into fixed and variable expenses.

Groceries, for example, are discretionary and variable because I plan my grocery list and determine what I eat. Utilities are also variable but they aren’t discretionary. While you may have a ballpark estimate of what your utilities cost each month, that’s not the case for everyone. Certainly not here in Texas.

Lumping your electric bill in with groceries as a “discretionary” expense makes it harder to plan your expenses in my opinion. You can make decisions to cut your grocery bill. But even if you limit your A/C usage in the summer months, the price of electricity isn’t really at your discretion.

By properly categorizing your income and expenses, the authors shed light on the true problem affecting independent workers. As they write:

“People like this don’t have an income problem. They have a cash flow problem.” (53)

The issue for many workers isn’t necessarily a lack of money, it’s the misallocation of it. When you don’t know what you have it’s hard to plan how to spend it. And if you don’t know how much you spend you don’t know how much you need to earn. That’s why knowing your income, expenses, and surplus is essential before you can put it to work.

Instead of budgeting around dollar values, The Money Book recommends that independent workers plan their spending around percentages.

The entire financial system proposed in the book is centered around percentages rather than dollar figures. This is actually quite a novel approach given how difficult it is to create a budget around irregular income that comes in at various times throughout the month.

This system begins with paying yourself – and Uncle Sam – first. There are three mandatory expenses all independent workers should take off the top of each check that comes in:

Taxes

Emergency Fund

Retirement

The authors recommend creating segregated accounts for these funds and I would concur with that recommendation. If you don’t see it, you can’t spend it. Personally, I have a business checking account that I use to receive my freelance checks. Within my business account, there is a sub account for taxes.

When I “pay” myself, I send my spending money and emergency fund allocation to my personal checking account. From there, anything I want to save is automatically deposited into a high-yield account on a recurring basis.

If you earn any income outside of a W2 job, it is essential to have segregated accounts. Having commingled my own funds in the past, I can personally attest that it not only makes it difficult to do important things like filing your taxes, but it makes the whole process of sorting through all of your transactions more time consuming and expensive too.

Aside from these three accounts, you should also have a fourth account – your spending account. This is your main checking account where you pay all your bills from: rent, groceries, gas, credit card payments, etc.

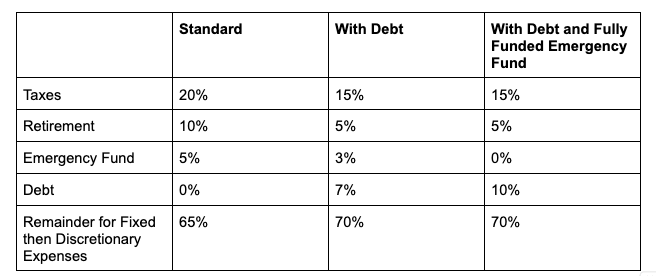

Once you have your accounts set up, the authors recommend using a percentage system. This means instead of budgeting based on a dollar figure, you budget based off of a percentage. Here are some of the recommended percentages provided by the authors in the book with some modifications made to reflect more realistic scenarios:

There are two important things to note about these suggested percentages:

Taxes will vary. Use your previous tax history to determine how much you actually need to pay. Last year I paid 20% of my gross income to Uncle Sam. You might pay less or you might pay more. I think 20% is a reasonable estimate for someone earning $50,000 or less. You can always adjust your percentage throughout the year to accommodate changes in your income.

Your emergency fund will also vary. Most financial experts recommend saving three to six months’ worth of expenses in an emergency fund. That way if you suddenly lose work – which you will if you’re a freelancer, rest assured – then you have cash in the bank to cover your expenses while you look for new work.

How much you need to save will come down to how much you spend each month to live your life. If you want to save a three-month emergency fund and you spend $3,000 per month, you’re going to need to save a lot less than someone who spends $10,000 per month. Once you’ve saved up what you need to save in your emergency fund, you can reallocate the percentage to something else like debt, saving for retirement, or planning a dream trip.

By developing a percentage-based budgeting system, you’re able to more effectively establish a hierarchy around your spending. Right off the bat you know anywhere from 25-35% of each check will go to your emergency fund, retirement, and Uncle Sam. After that, you need to prioritize your fixed monthly costs. Whatever remains is the money you get to live off of.

The authors use a flowchart to represent how your money should flow through your different spending priorities. This is a recreation of the flow chart I drew while taking notes from the book:

I personally like this system because it takes personal finances – which already tends to be disorganized and chaotic – and puts parameters around how to process your money.

When you know what you have to pay and in what order, it gives you more clarity around what you have left to spend. If you know you only have $50 in the bank until your next check comes in, you’re giving yourself the power to say no to the things you want in order to say yes to create a more stable situation for yourself in the present.

Final takeaway.

I decided to do a write-up of this book because I do think looking at money management through the lens of percentages is helpful, especially for workers with irregular income.

It’s important to remember that, at the end of the day no one, not even W2 workers, get to keep 100% of what they earn.

When you’re a freelancer, it’s easy to see a $1,000 check come in and spend all $1,00 of it. This book does a good job of reminding freelancers that they need to exercise greater discipline to make sure they’re saving for their future while also paying Uncle Sam.

That being said, I wouldn’t recommend this book to most readers. I think you can get the gist of it – a percentage based spending system – without the rest of the content offered in the book.

The book is too simplistic and offers a biased approach to financial management. My biggest issue is that the authors have a perspective of money that is incongruent with today’s generation of freelancers.

The authors began their respective careers in the early 1990s when college debt was practically nonexistent and the economy was otherwise good. As Morgan Housel writes in The Psychology of Money, the economy you are born into shapes how you view money and thus the nature of work. The authors' biases around money frames the entire system they promote and not necessarily in a good way.

Like most personal finance books written by late Baby Boomer/early Gen X authors, individuals are always blamed for their debt without acknowledging the debt-based system we all live in. While splurging on avocado toast at brunch might not be the best decision, it’s not the reason why you’re in debt.

When reflecting on personal financial decisions, the authors offer moral judgments that are quite tone deaf. They write:

“Vacations are lovely, but it’s not appropriate to toss 20 percent of your pay at a Bahamas getaway and a mere 5 percent to a down payment on a house or a child’s education.” (251-2)

The authors are two freelance writers sharing a system that worked for them. Who are they to decide what’s an appropriate way for you to spend your money?

At the end of the day your portfolio or the spreadsheet you track your finances on isn’t going to show up at your funeral but your family and friends will. If you want to take a “Bahamas getaway” to spend time with the people you love, who are the authors to tell you otherwise?

You have one life to live. The reason why many people go freelance is precisely for the freedom this line of work provides. If an arbitrary percentage is holding you back because the authors think it’s more “responsible” to buy a house in today’s market, what’s the point?

Managing debt – rather than providing wisdom on how to boost your income as a freelancer – is a primary focus of the book which brings me to the other problem I have with it. Throughout the book, the authors implore the reader to do whatever it takes to avoid debt while simultaneously noting that cash flow is a struggle for freelancers. They blame the reader for being in debt and provide no solutions for how to leverage their status as an independent worker to change their situation.

Unfortunately, as more and more workers become classified as independent workers, it’s becoming easier for employers to exploit them. Unlike W2 workers, freelancers don’t get to collect unemployment when a client pays late. Credit cards are the social safety net for most workers who don’t qualify for government benefits.

While the percentage system the authors recommend is a good idea, it also takes time to implement. Depending on where you are in your freelance career you may not have enough consistent cash flow coming in to make it work. That means for a period of time, you may have to drain your savings or go into debt.

If you’re new to personal finance or freelancing, this book may help. But if you’ve read a handful of personal finance books, you might want to skip this one. Most of the information is dated and while the percentage system is useful, you don’t need to read the entire book. Chapters 5-8 will provide you with the framework you need to set up this system for yourself.

That being said, if you want to read the book, you can check it out from your local library or order it from the link below.

Modern Adult is a member of Amazon’s affiliate program. If you click a link Modern Adult may earn a commission.